Goa Gajah, situated just south of the road between Peliatan and Bedulu, is clearly indicated by a concentration of curio shops. Today it seems difficult to believe that until 1922 or 1923 this well-advertised antiquity was known only to local people. It is even more remarkeble that only a comparatively short time ago an extensive watering place was discovered here – one whose existence was unsuspected even by villagers.

Goa Gajah was first mentioned in a report to the Archeological Service by L.C. Heyting, a young civil servant at Singaraja visiting Central Bali (1923) He referred to a “monster’s head with elephant’s ears”, deserving expert study. A similar reference ( “a cave overshadowed by an enormous elephant’s mouth”) led Nieuwenkamp to the Goa Gajah region dduring his third visit to Bali (1925). By this time Bali had been opened to visitors, and Nieuwenkamp could reach the Goa Gajah by then by motor car : a foreshadowing of things to come!

The name “Elephant Cave” perhaps originated with early visitors, mistakenly interpreting the monster’s head as an elephant, or from villagers with the same misunderstanding (or else refers to certain elephantine sculptures, presently discussed). There bmay also be a (much older) connection with a gajah. A Balinese place named Lwa Gajah, ‘Elephant Water’ is in fact mentioned in the 1365 Nagarakrtagama as the seat of a high Buddhist official. Since it occurs immediately after Badahulu (nearby Bedulu) this Lwa Gajah, named for some reason unknown to us, may very well have later given its name to the cave.

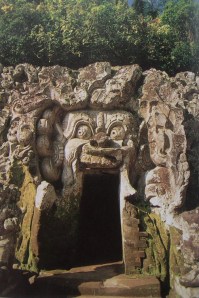

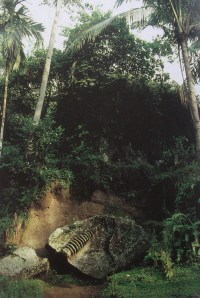

After his first visit to the site, Nieuwenkamp rightly had doubts about the head above the cave being an elephant’s. Its face was badly damaged. There was no sign of a trunk. Neither the ears nor the ear ornaments suggested an elephant. For some time the question remainde unanswered, but a clearing of the rock’s surface and recent restorations left no doubt about there being no elephant whatever in the rock wall.

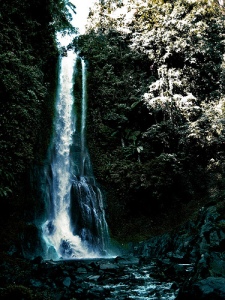

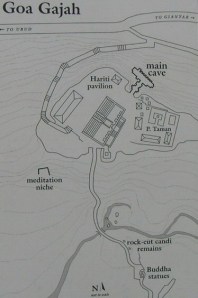

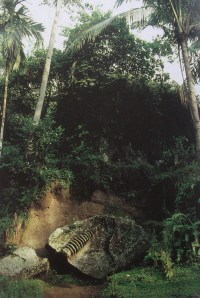

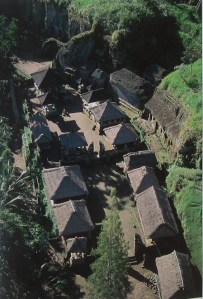

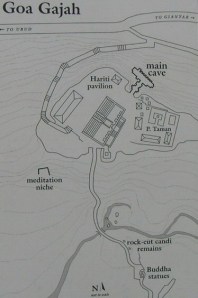

The cave lies south of the road , several meters below its level, and must be reached by a steep path. Whereas for a long time since its discovery, the situation of the Elephant Cave and the little pura in front of it had notably changed, the 1954 excavation of the watering place gave new character to the cave’s surroundings.

The interior cave was first reconnoitered by Nieuwenkamp, who paid no attention to bystanders’ remarks that “there was nothing inside”. The cave consists of a man-made T-shaped excavation opening to the south. Recent research has revealed that there may have been a stone screen (aling aling) in front of the cave’s entrance. Such screens saveguard dwellings and sanctuaries against evil influences. According to Balinese views, such influences may be expected from the south, which the cave faces. In Central and South Bali south is kelod, towards the sea and the Nether World, thus dangerous.

The entrance, 2 metrs high and only 1 meter wide, leads to a very dark interior. (a flashlight comes in handy here, but most of the time there is some obliging person around who will light up the darkness with an oil lamp for a small fee.) The T’s straight leg consists of a porch and a passage which together penetrate into the rock over a depth of around 9 meters.

The cave contains 15 niches hewn out of the walls. Some of them are long. They may have served as sleeping places. Those along the lateral passages are short and may have served several pusposes.

To the right of the entrance are two vagely engraved grafitty in the wall (inside), one above the other. The upper one seems older than the second and recalls the writing of an A.D. 1074 inscription. The meaning of the engravings is not clear. If the writing is correctly dated, the cave itself might have been made early in the 11th century. Sculptures found in the neighborhood cover a longer timespan.

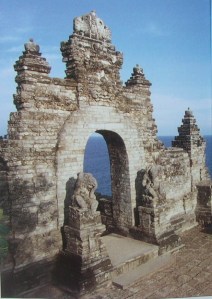

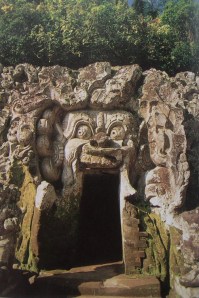

The cave has been cut into a projecting part of a rock wall whose surface was simultaneously streightened on eihter side , the more to emphasize the salient, which has a flat surface. The salient’s front and lateral faces are entirely covered with sculptures suggesting stylized mountain scenery interspersed with large and forcefully modeled leaves. Animals and monsters climb the rocks, peep around corners or comprise funny scenes. The animal kingdom is further represented by a snake in its hole, another highly stylized snake, a tortoise, and some indistinct animal. Two little figures climb a rock. One, whose loincloth is sliding down, has his genitals showing. In addition there are a monster’s head with pointed ears, a lingga. The baroque scene presents a mysterious mountain forest, set apart from the civilized world of human beings.

In the center of it all emerges the enormous monstrous face which ever since the early 1920s has intrigued visitors and which still leaves us with many questions. It most probably is a wich for the ear ornaments are female.The combination of a monster’s head and a hermit’s cave is also known in east-Java. If it originates from the kala heads over a candi’s entrance, it is a version turned fully Balinese: a real witch taken from the theatricals and impressed upon the rock. It is difficult to say whether this specific witch should be considered ‘threatening’. A Balinese, for that matter, likes threatening temple decorations, which make him feel safe from the dangerous powers repelled by the ugly faces. The witch seems to emerge with all her powers from the mysterious world enclosing her, and to which she belongs. In the 1950’s a large piece of the witch head which had fallen down was restored to its original place.

Until 1954 several figurative spouts stood on eigther side of the cave’s entrance: one shaped as a two-handed Ganesha, the others (6) as the upper halves of female figures. They evidently came from some watering place in the neighborhoud. In the early 1950’s the spouts were provisionally placed around a small pond not far from the cave. Water came from a well via an old tunnel parallel to the rock. But the spout figures did not fit this situation because there was no connection between the busts and the pond’s border. In 1954 the flat courtyard in front of the cave was excavated. Rock bottom was struck around 50 cm, without any soil finds other than the wall screen in front of the cave.

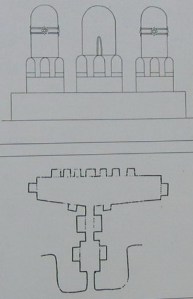

Acting on information received from locals, the field was widened with the border south of the cave. There, so was said, were some stone steps. The beginning of a three fold flight of steps was found, which after excavation led to a former watering place. It consists of two separate partions, probably one for women and one for men. Each formerly had been connected with a water system by three figurative spouts, shaped like standing nymphs. Only the lower part of these figures were still in situ. They proved to fit the upper parts found in front of the cave! The watering place could be restored and its original function re-established. The walls of the basins were renewed to construct an aestetically satisfactory and workable bathing unit. The back wall’s top is in a line with the courtyard in front of the cave. Part of the wall between the two groups of three spouting figures has not been restored; the narrow basin’s exact layout has not been ascertained. The Ganesha spout found with the other figures in front of the cave may have been situated in the middle basin and provisionally given a place there, albeit unconnected with the water system. The other spouting figures are fed from the original water system.

The lower part of the figures was carved from the living rock. Presumably, masses of earth, and carved stones from walls or gateways slipped down from the side of the stairs, eventually covering part of the figures. On top of this piled-up mass was situated a pura, which still partially exists. The loose upper parts apparently were taken away to be replaced in front of the cave. In the neighborhood of the cave several objects were also located: a pot-shaped stone object, two cylindrical stupas, and some pinnacles.

The discovery of the watering place was one of the gratest surprises of archeological work in Bali after World War II.

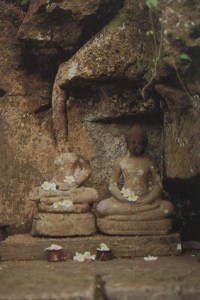

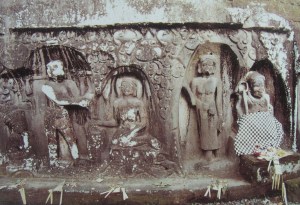

One of the pavillions in front of the cave harbors an image of the Buddhist goddes Hariti. A child-devouring ogress, she was converted to Buddhism, an she became a child protectress; she is always accompanied by quite a number of children. She is found in sanctuaries in India as well as elsewhwere in the Buddhist world. In Bali she acquired an established position – perhaps through aidentification with some indigenous legendary personage. In the ravine south of the cave, several parts of an enormous relief were discovered, the first in 1931. This relief evidently broke off the rock wall high above and slid down into the depths in pieces. After World War II some of the fragments were further exposed. Several more sculptured stone pieces were found in the neighborhood, in and around the affluent of the Petanu River, flowing from East to West along the Goa Gajah complex.

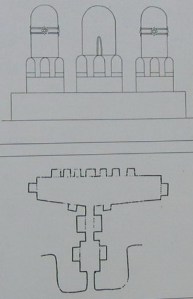

The fragments so far best known are two big pieces of stone, each around five meters broad. Their connection is not quite clear. The main subject on one of them is a fragmentary pillar decorated at the top, supporting a lotus cushion carrying a complicated system of stupas. Its central element is a stupa’s body, whose spherical shape seems to be compressed under the heavy weight of its pinnacle. The latter consists of an apparently octangular pedestal and a series of sunshades; of which four has survived.

The general arrangement resembles the candelabrum-shaped lotus stalks used to support Buddha images, niches for statuettes, or lamps, known from Ancient Java. At the very top of the fragment, the lower part of a Buddha image can still be vagely seen.

The relief is stylistically very different from the cave’s decoration, and is presumablymuch older. On the other hand, there is a general resemblance between the stupas on candelabrum –shaped branches and the lotus cushion-crowned Sanur pillar. The relief possibly dates from the same period, and might even have a certain connection wth King Kesari, who had the pillar made.

In the neighborhood of the fragmentsdescribed above is another relief showing a series of 13 umbrellas. It seems reasonable to suggest a realtion between the various pieces, though it is not yet established from which part of the original relief the 13 umbrellas originate. In the rock high above the location of the several fragments, a niche was noticed. This is far too small to have harbored the relief, which now mesures about 5 meters from right to left and must have been considerably larger. The relief may have been fallen either from the rock’s corner to the left of the niche, or from some point lower down.

Since the rock-cut candis were probably associated with the cult of deceased kings and their relations, there is reason to connect the enormous relief with a deceased king’s “monumentalization”. The arrangement of the stupas with their multitudinous sunshades recalls the various superimposed and juxtaposed heavens of later Balinese religion. In this case, the subject is a Buddhisst king. We do know of such an apparently Buddhist ruler, kesari of the Sanur pillar inscription. It was partially written in a specifically Buddhist Early Nagari script, on a shaft supporting a lotus cushion. This certainly recalls details from the Goa Gajah relief.

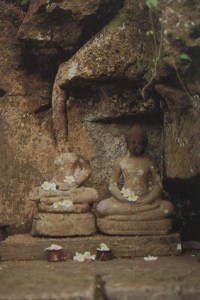

That would make this relief, as well as the Buddha statues, contemporaries of the Central Javanese period.